The History of Incino

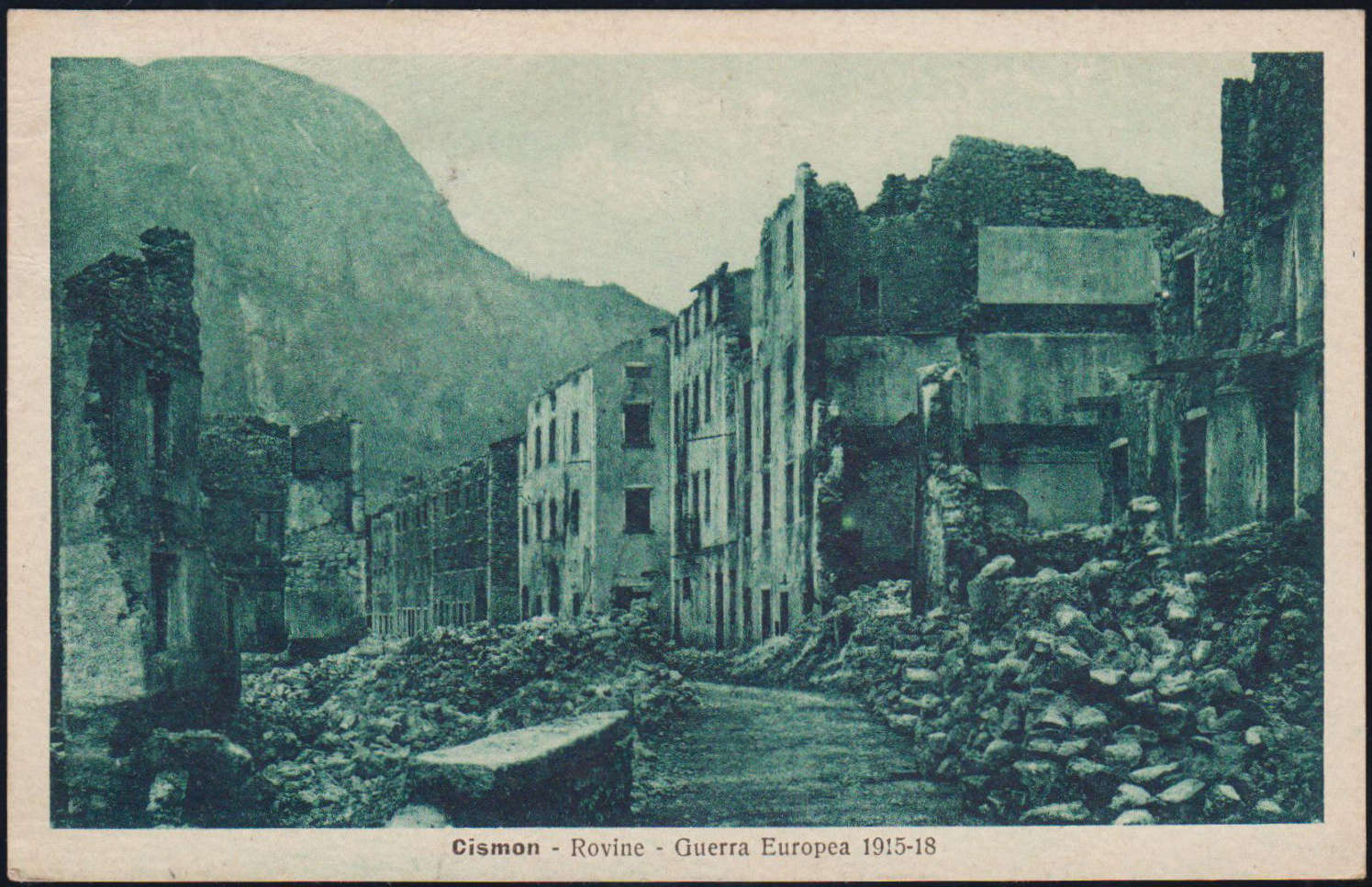

1919 – 1945: Fascist Era

Postwar

As soon as the war ended, the Italian government established a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Violations of the Rights of the People Committed by the Enemy. The data furnished by this commission showed that in the township of Arsiè, in exactly one year of Austro-German occupation, there were 480 deaths, subdivided thus:

- From hunger: 270 deaths

- From various illnesses: 200 deaths

- From enemy brutality: 10 deaths

At least 100 were children.

To rebuild the houses that were damaged or destroyed, carpenters from Incino’s Labor Cooperative were working out of the church. At the beginning of 1919, the Genio did a great deal of work to restore the church roof, the choir, and the bell tower. Seminarian Don Siro Nardino accompanied the commander of the Office of the Genio to Fonzaso to get the materials for stabilizing the church. After the renowned Don Giovanni, there was a slightly crippled priest who came for two Sundays, then our compatriot Don Modesto Zancanaro was sent to be the curate, where he stayed for almost two years.

1920

August 20

On the first visit from a bishop of Padua to Incino, Monsignor Pelizzo was on his way from Rocca when his car broke down. He had to reach Incino on foot, in the rain.

In this same year the Catholic Youth Circle springs up, under the patronage of Sant’Alfonso.

1921

Mail delivery begins in Incino. The job of mailman was given to Giovanna Zancanaro (“Nana Postina”), born 1892, who was 29 years old at the time and held the job until 1965 when she retired due to age limits. Her daughter Battistina Grando took her place, performing the job for the three years between 1965 and 1968, after which the mail was delivered by the mailman from Rocca.

This year the longest drought Incino has ever seen is recorded. It didn’t rain from June to December, and the harvest was almost nonexistent.

1922

July

Incino rejoiced as it saw its second son ascend to the alter, Don Siro Nardino, who committed himself brilliantly to the priesthood, teaching song and instructing children. He was ordained on July 16th, and on July 24th, almost privately, he celebrated his first mass in Incino.

Also in July, 1922, the priest Don Pietro Pertile, not especially experienced or forceful, came to lead this populace, who took advantage of his overly good and simple nature and compromised the priest’s honor and his mission.

1923

Around this year the first photograph is taken of Incino. The campanile is seen with the half-ruined pyramid of its steeple and two crumbling houses.

1924

To ensure adequate school space, the purchase of a building for the purpose was arranged for £38,000. With Note No. 5409 of April 30, 1925, the superintendent authorized the acquisition, whereby mortgage paperwork was filed. But the process ground to a halt after the town failed to guarantee the mortgage through a municipal surtax. Then a portion of it was going to have been tied to toll proceeds, but again to no avail. The effort was reprised once more in 1936, but it encountered yet greater problems—plus there was the war in Ethiopia.

November 14

A visit from the Bishop of Padua Elia Dalla Costa, who confirmed 27 youths. The village counted 472 residents.

1925

May 8

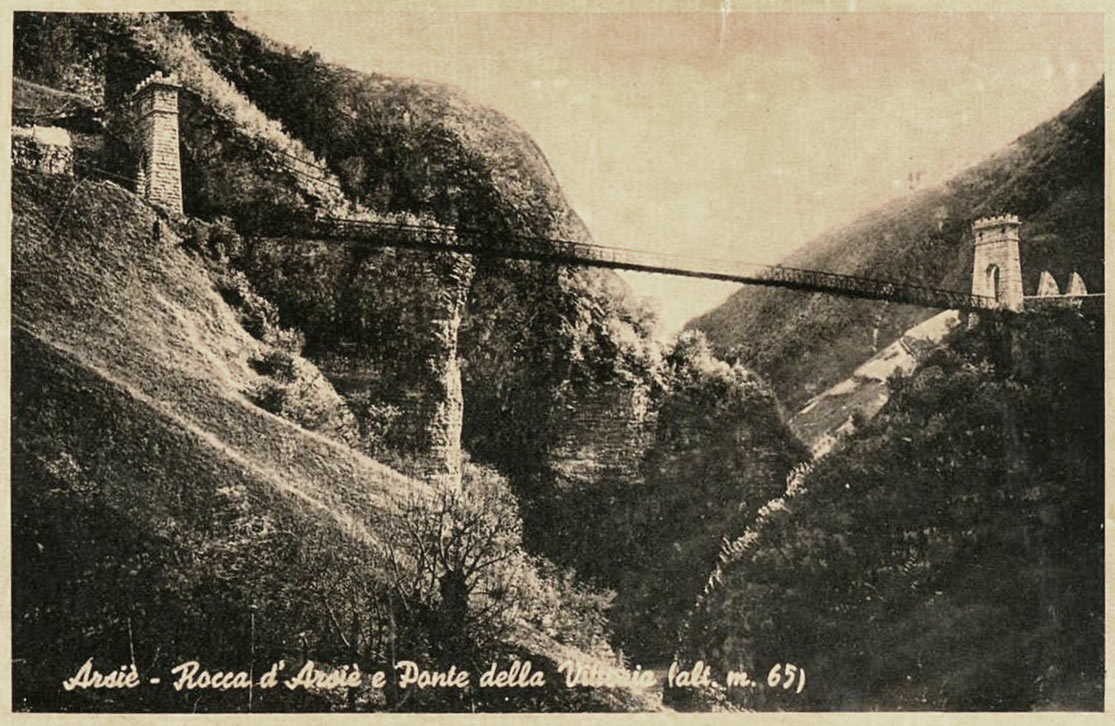

The town council approved the construction of the Pria Bridge out of reinforced concrete. The contract was awarded to the firm of Domenico Faoro (“Metolo”) from Arsiè. The cost of the work was £36,118. In 1954, the bridge was submerged under the waters of the lake. The project manager was Engineer Rasi di Feltre.

1926

With the royal decree of February 4, the office of podestà was established. From 1926 to 1928 the office was held by Dr. Sisto Zancanaro of Incino. On June 3, a market was established in Arsiè’s piazza on the third Saturday of each month. It existed briefly, then was reinstated in 1934, only to be cut back again, and ultimately it was cancelled. It was established in its current form, every Thursday, in 1948.

In 1927,

the second decennial celebration was held in honor of the Madonna della Salute. It was preceded by a triduum—three days of preaching—communion was truly universal, the church was crammed to the brink with people coming from throughout the surrounding area. Mortars were fired, arches, fireworks, the band from Arsiè played. In the evening in front of the church and along the Saccon there was a very successful lighting. At the moment the church was a subsidiary of the parish of Rocca, but the curate of Incino didn’t have any obligation toward Rocca’s pastor.

1928

The skilled hand of Giovanni Dalla Corte from Feltre completely refurbished our church, which had been reduced to a true hovel. He renovated the roof, the choir, the altars, the floor ruined by the horses. Pietro Bertapelle chiseled and polished the 4 steps of the balustrade that, with money from the parish councilors, he turned into 5. A larger basin for holy water was also installed, and much more could have been done if the heads of households and the priest had been shrewder.

The new bells, inferior in material and tone to the old ones, were cast by a firm in Milan and had the same names and weights: Domenico Zancanaro was the patron of the largest, Antonio Zancanaro (Meneghet), was the patron of the middle one, and the smallest was sponsored by several miners; they were then hoisted on cords to the belfry, reconstructed by Francesco Grando. The bells were manufactured, transported, and replaced on the campanile at the expense of the Ministry of Liberated Lands.

Then, under pressure from the Podestà of Arsiè Dr. Sisto Zancanaro, the little shrine was—with no small controversy—demolished and replaced by the niche of the Sacred Heart with an altar. Battistina Grando donated 300 lire. The statue of the Madonna del Pedancino should have been placed in the new niche, but Don Pietro had set aside the statue of the Sacred Heart instead. That had been given by Paolo Nardino, while the statue of San Rocco was donated by his son Giovanni. The statue of Saint Anthony was donated by Angelo Zancanaro, son of the late Arcangelo (“Scarper”), who made another present to the church: the statue of the Madonna del Pedancino. The cornices and the stained-glass windows were the work of Paolo Nardino and son.

Following Don Pietro Pertile, who stayed five years, was Don Federico Mazzocco, who had the altar of Pedancino built. The pews were made at a cost of £100 each. Finally, Incino was connected to the electrical grid for private use—in Arsiè it had come in 1910, and Rocca in 1922.

Curious, the Misadventure That Befell Don Pietro Pertile:

In 1923, Don Bernardino Rossi, Rocca’s pastor, bought a Fiat automobile, which aroused the admiration of all, but the pastor was having problems putting it into gear. One morning Don Pietro was passing through Rocca and was invited to get in. Don Bernardino first fought with the gears, which didn’t want to catch, then, with great exertion, put the car into reverse and let it go without pressing the brakes, rolling straight down a cliff. Of the two priests, Incino’s curate was practically unscathed but for the fright it gave him. More serious was the condition of Don Bernardino: battered, unable to speak, his face covered in blood.

In 1928, the prefect of Trento proposes annexing the townships of Arsiè, Fonzaso, Lamon, and Sovramonte to the province of Trento. On October 2, the town council of Arsiè declares itself absolutely opposed to this annexation and the proposal was dropped.

1929

Infant mortality takes a tragic toll this year. The dead are, in order: Assunta Zancanaro, 1 month old; Angela Zancanaro, 4 months old; Vittorino Zancanaro, 2 years old; Giustina Grando, 14 years old; and Antonio Zancanaro, 1 year old. We have to go back to 1904 to find such a high number of young victims.

1930

Since the year 1930, the baptism, confirmation, marriage, and death registers have been preserved in the archives. The decree establishing a subsidiary curacy was issued in 1929, and all jurisdiction was transferred by Rocca’s pastor Don Bernardino Rossi on March 1, 1930.

Don Giuseppe Carraro, who refinished the roof and bought an organ, arrived on February 3.

On November 8, 1930, there was a pastoral visit to Incino by the Bishop of Padua Monsignor Elia Della Costa. Here are some excerpts from the account of the curate:

The bishop arrived accompanied by Rocca’s pastor, during mass he administered 66 confirmations, at the end he gave a test of Christian Doctrine to 75 children.

There are exactly 500 residents, 87 families, at the holiday mass only 2–3 people were missing, two thirds went up for communion, morality is safeguarded, thank God there are no Jews, Protestants, Masons, spiritualists, or other sects in Incino. In the village there are no books contrary to faith, morals, and good customs. Every year, on the second Sunday of Lent, the anti-blasphemy festival takes place solemnly. In Incino there are no scandals, public or private, and no illegitimate children. The women don’t have time to follow fashion. Since 1928 the confraternities of the Holy Sacrament and the Daughters of Maria have been in existence, the latter with 25 members. Emigration is the true scourge of Incino, I would never encourage it, least of all for the young, but it can’t be stopped.

The church is only blessed, still not consecrated, it’s just 27 years old, but it’s not sufficient anymore for Incino’s population and we don’t know how to expand it.

This year Giuseppe Zancanaro, Zaccaria Grando, and Paolo Nardino were appointed to the parish council as treasurers. The Bishop was pleased and recommended that Don Federico give adequate instruction to the midwife (at the time Margherita Zancanaro) each year on how to administer Baptism in case the priest isn’t able to step in swiftly.

Starting this year we have decided to buy the hosts from the sisters of the rest home in Fonzaso and to no longer make them on site.

The Bishop orders that the electric lighting in the church be modified, removing the light bulbs forbidden by liturgy around the sacred images and in front of the tabernacle door, if you want to light the images in the niches, you can use, if you wish, a hidden bulb with modest light.

The offerings collected in Incino in 1930 are reported:

• For the Propagation of Faith: £95

• For the offering of Saint Peter: £50

• For the Catholic University: £125

• For the Holy Land: £18

• For the redemption of the Negroes: £10

• For the Holy Childhood: £15

• For the diocesan seminaries: £135

• For Catholic works: £21

1931

On July 29 at the age of 13, Camillo Zancanaro died, falling suddenly into the Cismon from Drio el Col.

1932

On November 20, Giovanna Bassani, 79 years old, fell from the Saccon (the current Mezzaluna) and plunged to the street below. She will die 24 hours later from “intestinal rupture.”

1933

For the 20th centennial of Christ’s death a series of cement crosses was built throughout Italy, said to eventually be visible from one another all the way to Rome. One can be seen at the southern point of Incino; another is on the Rocca Hill above the cemetery.

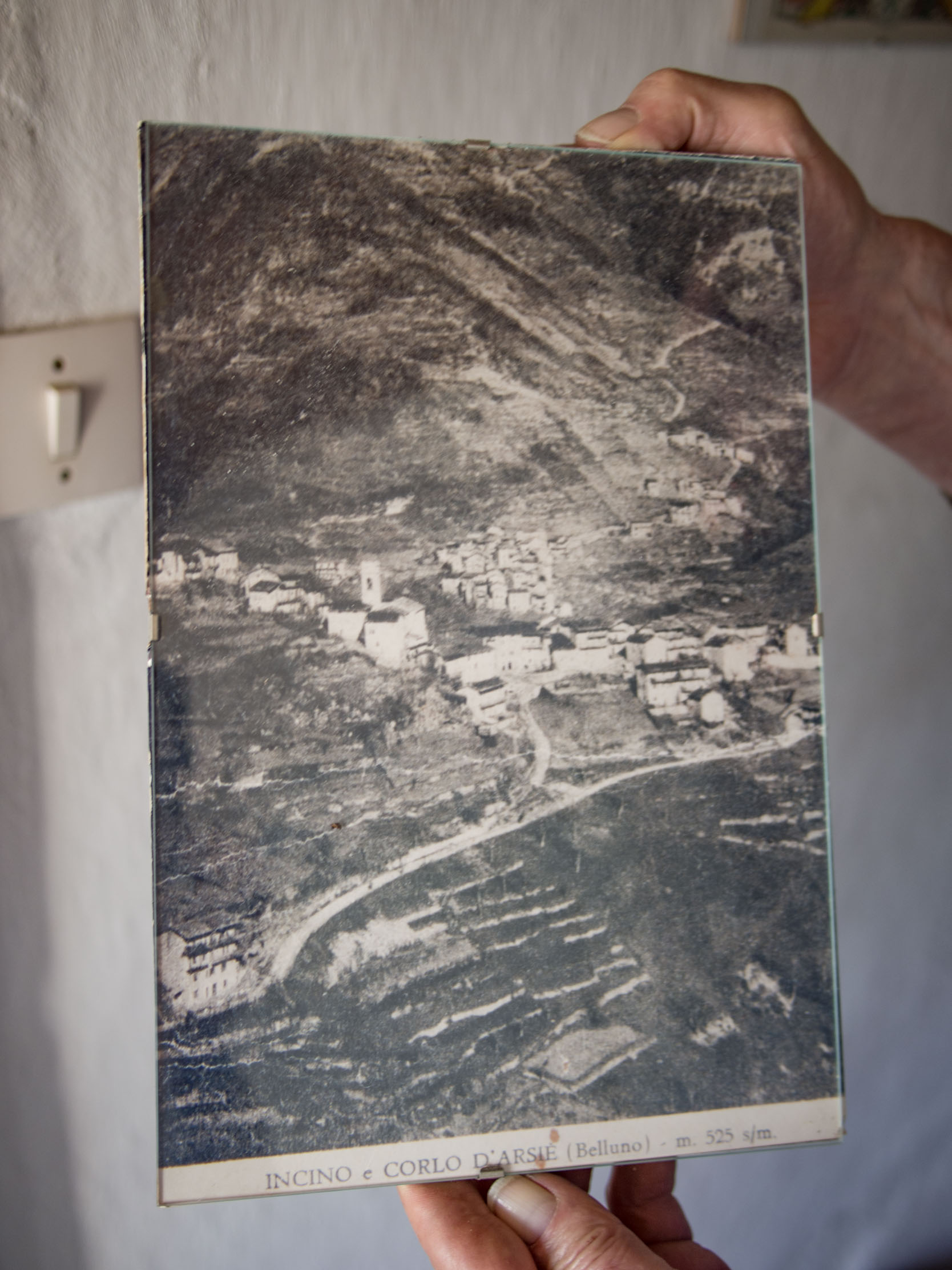

Also in 1933, we have the first known postcard of the village: it looks very similar to its current form. It was ascribed a height of 525 meters above sea level. This postcard was mailed from Cismon to France and is addressed to Camillo Borsa (“Quinto dei Bani”).

1934

The parsonage, owned by the village, is written over to the diocese of Padua.

1935

On April 3, Don Angelo Scarpin came to Incino as curate. He procured the funerary bier; the funerary shroud was donated by Don Siro.

In September of 1935, a printed letter was sent to all the emigrants from Incino (100 copies) exhorting them to keep their faith intact, to live like good Christians, and to find themselves in their church.

During the decennial celebrations of Arten (September 15–22) Bishop Agostini blessed the church banner, the excellent work of the sisters of Canossiane di Fonzaso and it was brought into procession for the first time by Domenico Grando, president of the nascent Catholic Action of Incino.

In 1935, in particular through the work of brothers Antonio and Erminio Zancanaro, both called “Casata,” the baptistry ceiling was built anew out of cement.

On the day of December 2, 1935, after a three-day triduum of preparation held by Archpriest Don Francesco Caron of Cismon, there was a pastoral visit from the new bishop Monsignor Carlo Agostini. Here are some excerpts from Don Angelo’s report:

Incino, 326 residents across 69 families, is a poor village, its scarce arable terrain is used for growing corn, beans, potatoes, and vines, the men beyond 13–14 years old have always emigrated abroad for work, so many that in summer more than a third of the houses are closed until late autumn when everyone returns, mostly from southern France. From the end of the Great War to today, 200 people have emigrated abroad, while 40 are workers who have left their families behind in Incino, though it must also be said that their parting is unavoidable.

The young girls generally go to the plain to work in the homes of the wealthy, but this year 15 set off directly for France, I’ve recommended that mothers not send anyone else off to work but no one listens.

This is the first year of the century that there are no weddings, there were two separations, but no other scandals, no one illegitimate, I often preach against prolonged and immoral flirtations but I haven’t heard about any. Everyone in the village is extremely poor, attendance at Sunday mass is almost universal, even on weekdays 50–60 believers take part, 6 copies of Difesa del Popolo come to the village [link in Italian]. These are the major vices: pride, rumormongering, foul language, onanism; blasphemy is not very widespread.

They say that it’s better to make 5 lire here than 15 abroad, the trouble is that 5 lire can’t actually be made here. There has been much debate recently about nuns possibly opening a nursery school (I’d heard the Canossians) but the problem is irresolvable due to the lack of potential sites.

Seven relics are kept in Incino’s church. They are: the Holy Cross, Saint Anthony, San Luigi, San Rocco, San Camillo di Lellis, Sant’Agnese, and one of the Madonna. The list is on display in the sacristy—the relic of the Holy Cross enjoys a special following. The sacristy, speaking of which, is a hole, the door is too low and there is no way to enlarge it, moreover it is always damp.

In Incino there are no deaf-mutes; there is, however, a poor moron and she was taught and admitted to the Sacraments. The curate is aware of: £600 from the population, £1,400 from the Church Coffers, and £1,000 from sacred-function fees.

1936

From September 24, 1936 to November 22, 1939, the curate was Don Angelo Rizzo, who sold the old parsonage for a price of £8,200. He gilded the throne of the Holy Sacrament. The teachers of Christian doctrine were awarded with a white chasuble with the seal of the bishop.

On May 5, 1936, Italian troops made a victorious entrance into Addis Ababa. During the campaign, Natale Zancanaro of Incino perished at Tembien.

On October 24, 1936, the school year began with 33 pupils attending, divided thus: 5 in first grade, 6 in second grade, 8 in third grade, 14 in fourth grade.

Starting November 22, the curate had more than 20 workers from the firm of Giuseppe Zancanaro (“Micel”) reconstruct the street out to the Cismon provincial road. In addition, repairs were made on the road to Casere and the road to Prai. The workers left the proceeds from the township to the church.

1937

On January 21, there was a solemn anniversary ceremony in honor of Natale Zancanaro, deceased in East Africa, volunteer in the Blackshirts. Taking part were armed guards from Arsiè with the banner of the National Fascist Party, some young fascists from Rocca and Incino, and all the schoolchildren with banner and flag. There wasn’t much snow in these winter months, and consequently there was less suffering from cold and hunger than in other years.

On May 14, 11-year-old Vich Mario, son of Vittorio, accidentally fell into the Cismon from Drio el Col, a height of 220 meters. His body was found in Carpanè (VI) on May 30.

Summer and autumn were rainier than anyone remembered in a long time—the damage in the fields was incalculable.

The town government sent a check for 500 lire to the curate of Incino, who was having financial difficulties and pressed the Minister of the Interior for an annual subsidy of £1,000. On October 2 the school year began with 32 pupils, of whom 11 were in first grade, 6 in second grade, 4 in third grade, and 11 in fourth grade.

On November 27, 1937, the third decennial celebration was held in honor of the Madonna della Salute. The Catholic daily Avvenire d’Italia dedicates a long article to it. Taking part in the procession were Knight Dr. Giuseppe Riva, along with the regional inspector of the Fascist Party Sisto Zancanaro. The homily was given by Don Siro Nardino, the band from Arsiè gave a commendable performance. At the conclusion, Rocca’s pastor thanked the population of Incino, whom he described as: poor in possessions, but very rich in faith.

Taking Stock of 1937

Births: 7, deaths: 5, weddings: 5, communions: 16,500, assets in treasury: £4,425.56, debts: £4,101.50, exceptional offerings and expenses due to the festivities.

Chronicle of 1938

March 1

Thanks to god, and to the poverty of the people, at Carnevale there was no carousing, dancing, or illicit amusement, though some young people from Incino went to Corlo where they danced until the morning of the following day, provoking the wrath of the curate. On March 27, during the sermon on the soul, 114.15 lire were collected, a comforting amount from a population of 222 people. On April 3 in Arsiè, the Federale visits from Belluno. Transportation is provided to help everyone reach the town seat, but here the girls don’t behave very responsibly and three youths from Incino come home the next day, accompanied by irresponsible delinquents.

May

For half the month, masses are held to pray for rain. A procession is even organized to the oratory of San Cassiano in Rocca, but due to the small turnout rainfall didn’t come. Then a second procession was organized to the Madonna del Pedancino in Cismon, which the entire population participated in, and the following evening there was a downpour.

September 19

Cantors from Arsego arrive on an excursion to Incino, and sing the 9:30 mass to perfection.

Sunday, September 25

The first mass was held at 4:00 in the morning to allow the people of Incino to go to Arsiè to witness Mussolini pass through. He was expected at 8:00 in the morning. Many men from Incino were asked to organize the occasion’s proceedings: triumphal arches were prepared and thousands of tricolor flags were flown.

October 17

The school year formally begins. There are 27 children in attendance, divided thus: 8 in first grade, 7 in second grade, 7 in third grade, 5 in fourth grade.

On the Evening of December 31

60 centimeters of snow fall.

Taking Stock of the Year

Births: 2, deaths: 1, weddings: none, communions: 12,800. Very dispiriting for the curate: there are 3,500 fewer than last year.

Chronicle of 1939

January 6

Children came to services with an ear of corn to donate toward the work on the kindergarten.

February 13

For three days at 9:00, at 12:00, and at 5:00 P.M., the bells of Incino ring in lugubrious tones over the death of Pope Pius XI.

March 2

This time they ring out at the same hours to announce the election of Pius XII.

May 9

From the results of a census, there is a population of 210 people. It rains for the whole month of May, the harvest is compromised.

June 23

At about 3:00 P.M., a strong storm damages the crop of grapes and corn.

August 1

A solemn mass is held because, thanks to God, our little ones escape infant paralysis.

August 15

A contract of sale is drawn up for the old parsonage. Giovanna Nardino (“Pota”) buys the entire building for £8,200 from Domenica Zancanaro’s firm. It was thus composed: on the ground floor a schoolroom, entry hall, kitchen, wine cellar. First floor: hall with six small bedrooms, with attic above. Starting today she takes possession of it in the name of her mother, Cristina Nardino.

September 4

The teleferica, the cableway from Drio el Col that connected Incino and Corlo began regular operation after being blessed. It was used to transport large wooden beams. The proprietor is Mr. Rigoni from Asiago.

September 17

On Sunday at 1:15 P.M., twelve-year-old Vich Romano, son of Vittorio, was playing with the brothers Giovanni and Mario Nardino, swinging on the big cord of the cableway, when the metal cable detached from the wheel and swept the three boys into the abyss.

Thanks to the nimble sprinting of a certain Giacomo Zancanaro, 25-year-old son of Giacomo, the Nardino brothers were miraculously saved, while Vich Romano was cast from the cable into the swollen waters of the Cismon from around 220 meters above. The young Leone Zancanaro (son of Rodolfo), hoping to help Vich, rushed down to the river and was crossing the rocky bank when he suddenly slipped, falling about 28 meters down. Through the intervention of a few brave people and their cousins he was collected, although he was badly injured. Meanwhile, the body of poor Vich still hadn’t been tracked down. (It was recovered 7 days later in Rivalta.) The terrible accident anguished all the families in the hamlet, and the tragic end of her third child brought Romano’s mother to the brink of despair.

October 17

Regular school begins, 23 children are in attendance.

October 22

Due to the rain, only 25 faithful from Incino go to Arsiè for the closing of the Enego-Arsiè Interdiocesan Eucharistic Congress.

November 22

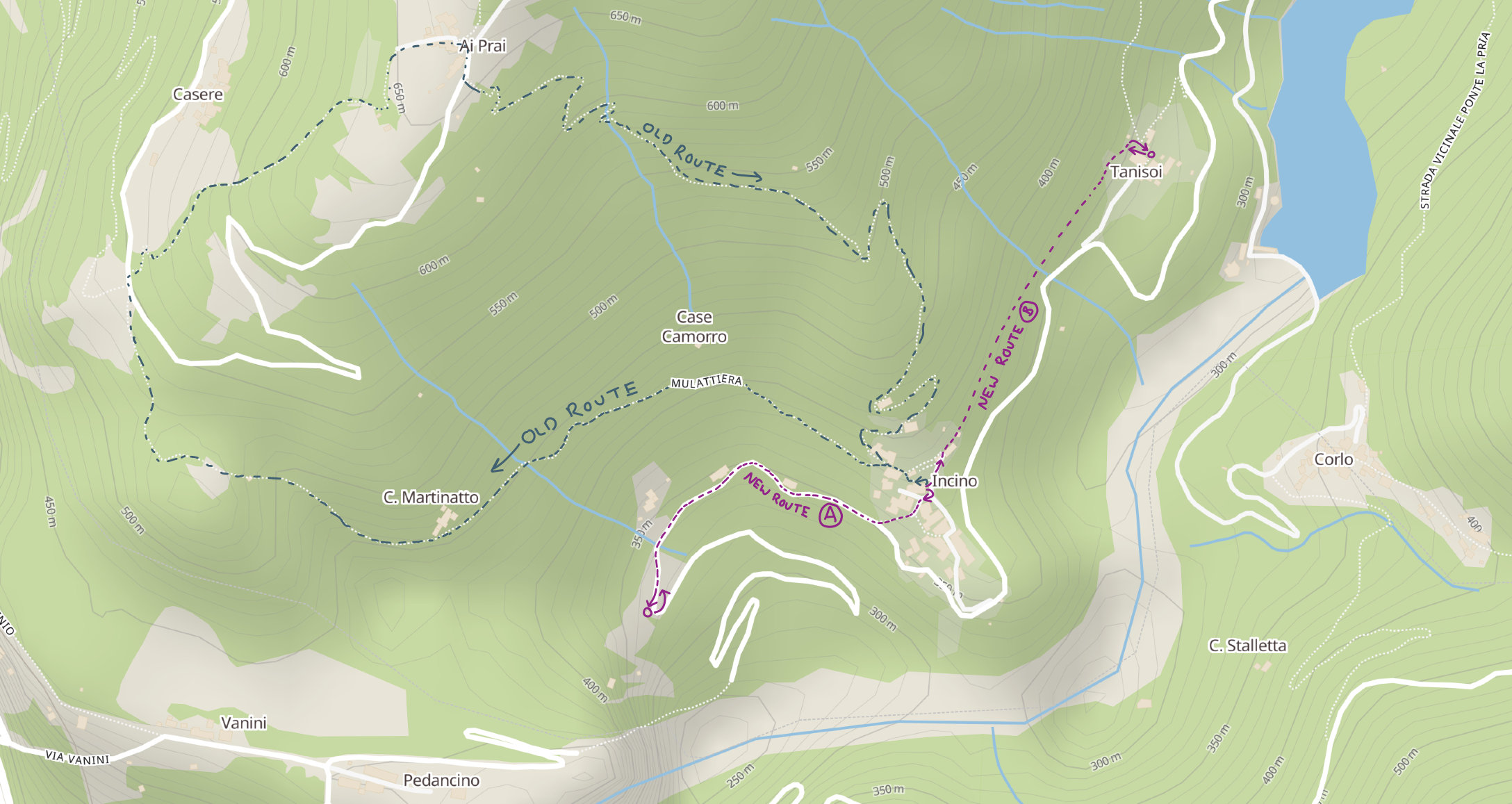

The departure of curate Don Angelo and concurrent arrival of Don Ernesto. Don Angelo’s final decision was a radical modification of the procession route. The route for Rogations had always been: Church, Martinati, Prai, Costa, and back to Church. It was noted for its excessive climb and length and was exhausting for many worshippers. Some elders would return to the village two hours late, after the celebrations had ended.

So a new route was set: Church to Somanzin one time, then Church to Tanisoi the next. It was the same route as the procession of Corpus Domini , while for Good Friday, since the procession was at night, it would go only up to Drio el Col. There were protestations and grumblings, largely because people feared losing the good grace of processions passing by their own property, but the curate was steadfast in his decision, and it remained in effect until the time of Don Eugenio.

From November 22nd, 1939 to August 10th, 1942, Don Ernesto Zuccato was Incino’s curate. During his tenure there were numerous works completed: the wall behind the choir was repaired, two walls were built in the baptistry, a marble tabernacle was purchased in Cismon for £1,500.

Finally, an endowment was secured for a the curacy: £30,000 in capital deposited in the curia at 5%, £1,000 annually from the township in perpetuity, plus wood and grapes furnished free of charge by the population in sufficient quantity.

As Don Angelo Left Incino, He Left This Account:

The life of the curate in the curacy of Incino is as poor as you want, in all respects. All curates come against their will and leave contented, the population is religious, though a bit coarse: some families don’t do their duty, some girls are immodest, possibly influenced by times that are highly wicked and corrupt, so the priest has the job of watching over and correcting without sparing the rod (in a moral sense).

Little news during wartime

1940

April 15

The last group of men departs for Colle Isarco (Brenner) this morning. Only women, children, and 30 elderly men are left in the village.

All the men are enlisted or at work on the fortifications in Brenner and Ventimiglia. At Colle Iscaro on October 24, 1940, Giacomo Zancanaro, son of Domenico (“Cici”), is killed by a mine.

On June 11, 1940, Italy enters into war, invading France. In the Battle of the Alps only one man from Incino took part: Gelindo Zancanaro (“Scarper”), who emerged unharmed.

1941

This was a full year of war, and due to scarcity everything was being rationed. On the other hand, God did not let any soldiers from Incino die—only Giovanni Nardino (“Camel”) was lightly wounded on the Greek front.

October 24

There is a strong presence of soldiers in Incino, who are quartered in the parsonage. Some young girls are being flirtatious, wearing short skirts, coming to church over and over due to idle lives.

1942

In the third year of war, the residents live solely off of ration cards: a kilo of bread and some grains of rice or pasta. Some families go hungry.

On February 15, the old sexton Luigi Zancanaro, son of the late Giuseppe (“Cul”), gave up his post out of infirmity. Italia Nardino and his 15-year-old son Giovanni succeeded him. Again the population was blessed by the Lord, since no one died on the battlefield and no one was injured. The blessing of the houses didn’t take place this year. The reason: the daughters of 5 families (3 from Incino, 2 from Prai) invited people home on several nights, playing the accordion and dancing until late into the night.

On July 26 the bishop’s decree creating an autonomous curacy in Incino was read in church. From this day forth, Incino is no longer dependent on Rocca. And parish priest Don Alfredo Dal Santo suspended ringing the bells as Incino’s dead arrived in the cemetery in Rocca.

This year marks the passing of two of Incino’s oldest-ever women: Tesera Smaniotto (“Cana”), born 1846, who was 96 years old, and on August 4 Maria Domenica Strappazzon, born 1845, who was 97.

1943

September 8

The little village rejoiced for a few hours at the news of the armistice—joy overshadowed immediately by gloomy foreboding. On September 10 an order from Adolf Hitler combined the provinces of Bolzano, Trento, and Belluno into the region of Alpenvorland, or the Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills, which were annexed directly to the Third Reich. The administration of this territory was assigned to Commissar Franz Hofer, an Austrian Nazi who established his headquarters in Bolzano—consequently, the new border between Italy and Germany ran across the Pala della Renga.

November 10

The second pastoral visit from the Bishop of Padua Carlo Agostini. Here is how Don Carlo Marini presents the situation in Incino:

Too many emigrants returning from France are cold and indifferent to faith, and their attitude is a very poor example for my parishioners, also deplorable is the wave of unseemly fashion in Incino, I have done everything to get rid of it, up to standing at the church door and not letting anyone enter with short dresses and uncovered arms or whatever goes against the dictates of the church. It is highly troubling to hear even the women cursing with “damn,” “dammit,” and so on. Here they live in extreme poverty, basically everyone is poor due to drought, this year there are even more food shortages, the cooperative in Incino sells only bread rations and some “sardela soto sal,” sardines in salt, one in two can’t pay for funerals, and nobody has money to arrange masses for their dead.

Sometimes people go to Cismon to do a little shopping but they take advantage by going to the cinema, so in church I always have to raise my voice because this is forbidden, at least for children and teenagers. There isn’t any recreation or amusement here, dancing is a veritable school of corruption and everything is done to thwart it: preaching, threatening, withholding house blessings, but it’s all useless. Now it’s necessary to counter the vice of limiting offspring as well, the causes: the war, the curtailment of everything, the men in danger at the front, in preaching and especially in confession I try hard to quash these attitudes, as though emigration weren’t enough to depopulate the village!

There are no intellectuals, professionals, or even skilled workers in Incino. The curate my predecessor (Don Ernesto) was accused of being too bitter, with a harsh energy and manner both in private and at the pulpit, and his position was finally highly compromised. The bishop, in his address, was saddened by young women going out into the world, quickly absorbing the worldly spirit, and deviating from old-fashioned simplicity to bring modern and scandalous ways of dress back to these mountains.

At the end of the year there are 303 residents in Incino, 71 families, no concubinage but two impossible-to-deter separations.

1944

In the month of May the first units of the Organization Todt arrived in Rocca and Incino. It was rumored that the Germans would continue the work on the Cismon-Incino-Rocca-Arsiè rail line, but instead they started building fortifications that would give the enemy substantial defense and protection in case of retreat.

On July 19 the German police station in Feltre, collaborating with Italian spies, commits a merciless act of retaliation, arresting 37 people who are imprisoned and deported to concentration camps and killing another 5: Lieutenant Colonel Angelo Zancanaro and his 19-year-old son Luciano are shot dead in the landing of the staircase of the Hotel Feltre. This episode, known as the “Night of Santa Marina” is the most tragic of the Nazi domination of Feltre.

Angelo Zancanaro, officer of the Alpini, led the partisan resistance movement in Feltre. He was born in Incino in 1884, the son of Giacomo and Antonia Zancanaro. He was decorated many times over and won seven medals of military valor: a bronze medal in the First World War for attacking an Austrian barricade as second lieutenant in the 3rd Alpini regiment; a silver medal in the same war as captain in the 9th Arditi regiment for conquering an enemy position on Col Moschin with his division—with a danger-defying, lightning-fast strike on June 19, 1918 they captured 27 officers, 250 troops, and 17 machine guns.

Three more bronze medals came from the war in Ethiopia. In the Second World War he was given another bronze medal from an armed skirmish at the Greek front on Monte Golico where he was wounded in his leg.

33 years after his death, on November 6, 1977, with a solemn ceremony at the Zannatelli military barracks in Feltre, he was awarded a posthumous gold medal of military valor [link in Italian], which was collected by his widow Mrs. Margherita and subsequently donated in his honor to the city of Feltre, where it is kept in the Museum of Italian Unification.

July 24, 1944

The eyes of Incino’s residents were met with a truly tragic sight: the burning of a vast number of houses in Corlo, 22 in all. The work of Germans.

Sunday, September 24, 1944

In the evening the Germans conducted a roundup. 20 men from Incino were loaded into a truck late in the evening—curate included—and spent the night in Rocca at the Bar dalla Corona. In the morning, after their papers are examined they are set free. Incino was put under curfew: circulation was permitted from 9:00 A.M. to 11:00 A.M. and from 3:00 P.M. to 5:00 P.M..

On September 25, villager Natale Zancanaro, son of Giobatta (“Tino”), died in Pederobba (TV). The news was learned one month later. In the report of the royal Carabinieri in Arsiè it is written:

Natale Zancanaro was on Monte Grappa when he was rounded up and identified as a resistance fighter, arrested, and taken to Penderobba, where he was hanged that same day.

His sacrifice is commemorated with a marble marker on the road from Onigo to Levada bearing the text Zancanaro Natale, 18 years old, martyr for freedom, Penderobba September 25, 1944 and by a marble memorial plaque on a building still on Via Roma.

There was a harsh winter between 1944 and 1945: bakers went without flour, daily black bread rations were reduced to 150 grams per person, without salt. When there was flour, there would be no wood. The houses and makeshift classrooms were freezing—the existing classrooms were housing the Germans. Very few attended school for fear of airstrikes.

1945

Sunday, May 1

The Incinesi, returning from a funeral in Rocca (for Pietro “Conco” Nardino) discover, back in the village, the first English and American soldiers, prompting a great celebration—additionally because two babies are born that day: Luigi Nardino (to Teresina) and Angela Campanaro (“Lina”).

May 9

There is a solemn Te Deum of thanks.

Sunday, May 13

Out of gratitude for having escaped the dangers of the war, the shrine of Somanzin was built, dedicated to the Madonna of Lourdes. Everyone contributed to its construction, hauling stones, sand, working as masons and builders. Statues were placed inside: the Madonna was donated by Laura Zancanaro, Saint Anthony of Padua was donated by Angelo Antonio Zancanaro, and Saint Joseph was donated by Romano Zancanaro.

During the construction, news came that Mario Zancanaro from Casere had died from tuberculosis on June 1, 1944 at the Lamsdorf military hospital in Germany.

All of Incino’s soldiers returned except for Ermenegildo Zancanaro (“Gildo from Prai”), who was one of 28 servicemen from Arsiè officially declared missing.

At the end of the year, Bishop of Padua Monsignor Agostini directs the episcopal curia to send out a survey of the events in the individual parishes during the war. Below, reported in full, are the responses that Incino’s curate Don Carlo Marini sent to Padua:

Moral Part

The refugees here in Incino come to 42, of whom 37 are from Cismon and 5 are from Turin. Prisoners (under the English or Americans): 11. Interned in Germany: 9 in the concentration camps and 4 as laborers. Poor (truly poor): none, poor (materially poor): 7.

Initiatives

The refugees were immersed in the religious life of the village, their children were taught doctrine alongside the others, houses were found for most of the refugees, and the five from Turin were settled in Incino with jobs at the Lancia factory in Cismon [link in Italian]. They were given homes, wood, flour, beans, potatoes, and assistance from time to time. Another three of the neediest refugees from Cismon were given additional help from the curate and two private families.

Nothing could be done for the prisoners except write several times over to the Red Cross and the Vatican. The imprisoned soldiers kept in bimonthly correspondence with us for as long as possible and we sent them booklets, mementos, etc.

Cash handouts were given to the poor (Saint Anthony’s Bread offerings, three times per month) and others were sent to the Todt cafeteria. Incino, especially in the last year, generally didn’t go hungry because it was helped in a thousand ways by O.T.’s wages and cafeteria. Around 150 workers from Rosà, Asolo, and Castelletto Vicentino were working in Incino.

Religious assistance

To make the Sunday precept easier, the first mass was held very early in the morning and the second was held at 3:00–4:00 in the afternoon. On village holidays there were three nights of special sermons. In general the O.T. workers had very serious demeanors; there wasn’t any dancing or other scandals, the church was full on every holiday. Dangers: the diminishment of holidays with respect to the Sunday rest (work was compulsory); a certain eagerness for amusement right after the insurgency—an attempt at dancing on the day of peace was thoroughly quashed only by the presence of the priest, who, without saying a word, stopped and watched sternly at close range.

Bombardments

Here in Incino, none—though bombs for Cismon’s bridges ended up falling on Martinati and Casere, so almost everyone was always lining up in fear in the numerous well protected tunnels here. There was machine-gun fire on Cismon’s bridges and consequently bullets hit Incino several times. One person was struck by a machine gun from the partisan resistance on Grappa, his arm and thigh bone shot through, another was shot in the foot.

Roundups

There was one in Incino and Corlo on July 24, 1944, the same day that around 25 houses were burned in Corlo. Incino, thank God, was spared completely in the fire and slaughter. There was another roundup on September 19, 1944, where 15 villagers were deported to Rocca along with their curate, who the next day got to spend eight days imprisoned in the same parsonage as his parishioners. It was under these circumstances that a parishioner, Natale Zancanaro, son of Giovanni Battista, lost his life on Grappa in the partisan resistance. Others miraculously evaded death, like Grando […] son of the late Giuseppe, who was going to be shot but was then set free.

Material Part

Work performed

The wooden pews in the church presbytery, other improvements for the pastoral visit, finally the shrine to the Madonna at a bend in the road for the processions of Corpus Domini, rogations, and in times of drought. The village had made a vow to the Madonna during the German retreat, and Incino, though in grave danger, suffered no deaths. The shrine (3 meters wide by 4 meters long) now has a roof, the whole village contributed. The parsonage had about 10 broken flagstones from bombings, plus three crumbling ceilings for the same reason. They are now being fixed, no idea the cost but certainly not large (two or three days for a mason).

Personal Part

The curate suffered somewhat through machine-gun fire, roundups, and bombardments, but no serious injury. In the roundup on September 19, 1944, he was taken as well, loaded with the others on a truck and driven to Rocca where he spent the night in a tavern. He was released with the parishioners the following morning, and they were put under watch in the parsonage, though through gifts he was able to buy permission to celebrate holy mass.

From October 4, 1942 to November 10, 1948, Don Carlo Marini from Carrè (VI) was curate. During his tenure the shrine was completed, the vow from the war, and he had the steps built around the church. The whole parsonage was redone with the fence out front and the retaining wall. The six large chandeliers were donated by Matteo Zancanaro. £62,000 had been put away as an endowment for the curate, but the war completely destroyed the little endowment, so the bishop wasn’t able to send another curate in his place.