Appendix

1817: The Uprising

In order to understand the events of 1816 in Incino, we must open with a small general preface:

1815

All the history books consider the Congress of Vienna to be the most important event of the year. The summit that will stabilize Europe after the end of the Napoleonic era achieves preeminence only because an event that occurred in Asia went almost unnoticed in the rest of the world.

In the next two years, however, it will cause formidable devastation.

Toward sunset on April 11, a volcano called Tambora in the Dutch East Indies (today Indonesia), literally exploded with violent rumbling (the boom from the eruption is thought to be the loudest sound ever heard by man). Over 5 days the eruption projected at least 300 billion cubic meters of ash, rocks, and other material into the air. The volcano, which before the eruption rose more than 4,100 meters, shrank by around 1,300 meters to its current height of 2,850 meters.

It was a calamity: 10,000 deaths were caused directly, but another 80,000 would fall victim in the weeks following the explosion. For several days, the sky was blacked out throughout the region. There was no quick way to transmit the news to the rest of the world, so the disaster was only known locally for some time. In New York they learned something only around October, while in London the news started to circulate around Christmas. Thus the news, patchy as it was, went almost unnoticed.

Meanwhile, the dust launched into the air by the volcano reached the stratosphere, where, transported by the prevailing winds, it spread across the planet, preventing a good part of the sun’s radiation from reaching the ground. Global temperatures fell everywhere as sunlight struggled to penetrate the atmosphere. The climatic devastation began in North America, Canada, and Northern Europe in the spring of 1816. Sharp and abrupt changes in temperature became common, snow fell during summer, by May ice destroyed most of the crop save for cold-hardy vegetables.

People everywhere were struck by severe destitution. Agriculture was crippled. In Europe, there were food riots in Great Britain and France and numerous stores were looted. In Switzerland the government was forced to declare a national emergency, but the entire continent was hit by freak rains, immense storms, and flooding of major rivers. The dust from Tambora remained in the atmosphere for many years, reducing the amount of solar radiation that would normally reach the earth’s soil. The planet would experience two years without summers and suffer unusually frigid winters, resulting in the scarcest harvest and widespread poverty in great swaths of the world. Because of all of this, 1816 was remembered as the year without summer.

This is the general picture in our area as well. The absent summer of the year 1816 brought about a great famine that affected the entire Feltrino. To revive the depleted economy, Austria intervened with considerable aid, permitted the growing of tobacco, which until then had been highly prohibited, and embarked on many public works, the most important of which was the straight stretch of the Culliada road. But hunger literally decimated the population. Here is an overview:

Wherever the spike in deaths in 1817 is noted, almost all are entered under the heading “starvation,” while the number of deaths plunge the following year.

Here Is What Happened in Incino, Taken in Whole from:

Rebels, Beggars, and Bandits

Rural Protests in the Veneto and Fruili, 1814-1866

by Piero Brunello

Marsilio Editori, Padua, 1981. Pages 156-162.

The first known talk of mobilizing to seize grain and flour was at the beginning of May, 1817. Around two months were left before harvest, the corn crop was far from ready. By that point there had been famine for three years.

A young man from Incino was on his way to Bassano to pawn something (we don’t know whether it was with a usurer or at the Mount of Piety), and on the road he spoke to a man from Rocca who was himself looking for a loan. The man from Incino, Giuseppe Grando, revealed to Gregorio Bellaver that the plan of action was ready. He didn’t say who would give the signal, but there was without a doubt “an individual designated to notify and gather the others in order to seize grain and flour.” Who this individual was was unknown, and it was precisely this secret that gave the scheme its mysterious and threatening air.

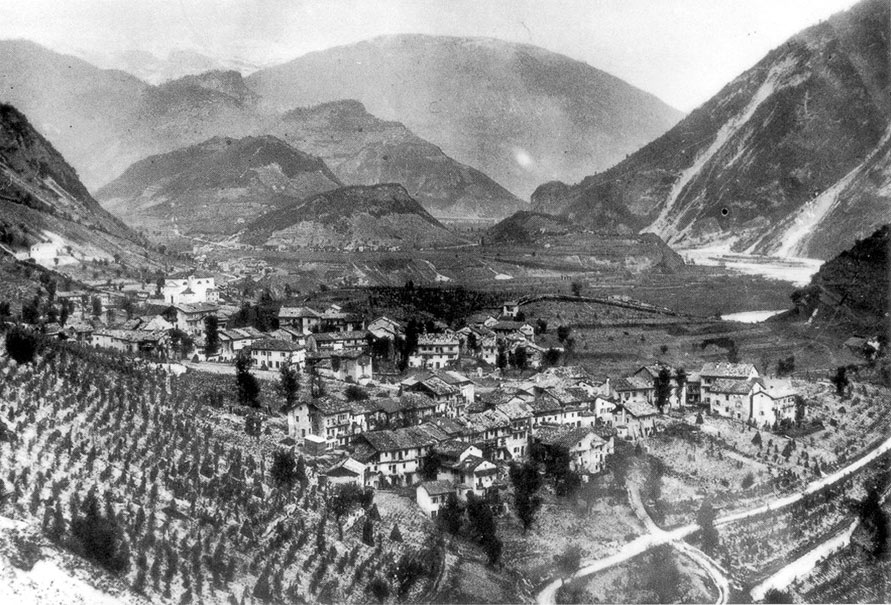

Knowledge of the setting will help to explain the events. Incino is a minuscule cluster of houses perched on the crest of a hill about 400 meters high. A road from Cismon in Val Sugana climbs up to the village, then descends to Rocca and finally down to Arsiè in the district of Fonzaso. From the top of Incino, the Cismon Torrent can be spotted running through a gorge toward Val Sugana. All around the village only terraces held up by drystone walls permit the cultivation of grapes, beans, corn, and potatoes. The lines of the terraces are still visible today despite the continued encroachment of forest, wresting the soil from the vines.

For more extensive meadows and pastures, albeit modestly, we have to go down to Rocca—or rather we would have had to, since an artificial lake built arrogantly and unscrupulously by SADE three decades ago has submerged the old village of Rocca along with its surrounding land. We mustn’t picture Rocca as a fertile plain—it, too, was a village squeezed between mountains. But at that point the valley widened and leveled out, giving the village a major advantage over Incino.

Since they shared the same valley, it might seem that relations between Rocca and Incino were very close. However, contrary to appearances, Incino gravitated toward Val Sugana below, which accounts for its residents’ aversion to Rocca, on which they were dependent administratively. That aversion is behind an old grudge that is remembered to this day.

One example of this is the “danger” incurred by Incinesi wanting to marry a girl from Rocca or vice versa, while at the same time marriage was common between the young people of Incino and Cismon. If you ask the reason, in Incino’s only tavern, for the affinitity with the Cismonesi, you will hear that both are “hotheads” and “revolutionaries,” and to support this assessment they will remember how in Cismon soon after the war they established an independent republic that minted its own money [link in Italian].

The fact that the mob gathered on Monday, May 19 suggests that the plan had been discussed in the usual Sunday meetings after mass or in the tavern. That Monday was also a holiday. In Rocca, the municipal seat, there would be a religious procession and many people from the villages of Incino, Berti, and Corlo were likely to attend.

Around 6:00 A.M. on that Monday, May 19, ten men from Incino went down to the house of Gervasio Arboit, the Town Deputy of Rocca. Arboit’s wife, Angela, happened to be tending to cattle in the stable, home alone, since her husband was already working in the fields at that hour. To grasp the purpose of their visit, it might have been enough to notice the empty sacks each man carried on his shoulder, but the woman asked anyway why they had come to her house.

They were looking for the Town Deputy, they said—and they wanted sorghum.

There wasn’t any sorghum in the house, answered Angela Arboit.

That doesn’t matter, the others replied, “the Deputy will come with us and he will retrieve it.”

Nobody knows what these ten, twelve men from Incino did next, and not even the Chancellor of the Census of Fonzaso, Mengotti, will take the trouble to ask about it in the course of his questioning. They probably returned to Incino to gather people. It’s less than an hour on foot between the two villages, and it would make sense since we know that just after 8:00, between 60 and 80 people showed up in the piazza in Rocca—almost entirely from Incino.

The pastor Don Giuseppe Leonardi, who was in the parsonage chatting with the Town Councilor Giacomo Grando while waiting for mass, saw them arrive in the piazza. After a moment of initial confusion, Giacomo Grando realized what they were doing there: they hadn’t come for the procession but “had risen up from hunger.” There were whole families, with fathers and mothers and children, and someone was carrying a big cudgel.

The fact that all the witness unanimously remember the detail of the cudgel suggests that it provoked a certain apprehension. But the pastor will explain during his testimony that the cudgel served “to sustain them through their weakened state.”

Don Leonardi and the Town Councilor went out onto the piazza. Amidst a great clamor everyone gathered around them. A voice from somewhere—later said to be the pastor—called out that they wanted to go look for assistance and relief. The pastor tried to get them to back down from their intentions, warning them that they were committing a serious crime that would be subject to “harsh punishment” under the law.

They had nothing more to fear at this point, they answered, since one form of death was worth the same as another and if the pastor and the Town Councilor were going to continue in their lectures they should take them somewhere they were wanted. The pastor was about to send for the Town Deputy—after all, it was his job to resolve the matter—when Gervasio Arboit entered the piazza on his own, having learned from his wife that the insurgents wanted to sound the alarm bells.

More attempts to get them to back down: flattery, good intentions, promises. No luck—the insurgents didn’t want to leave. Only some immediate assistance, the pastor will explain, could have assuaged them. While Don Leonardi stayed in the piazza, Gervasio Arboit and Councilor Giacomo Grando went to seek cornmeal and cheese among the best families of Rocca and Arsiè.

For the hungry people, it was a long wait for their return. While they were awaiting relief, recounted the pastor, a certain Antonio Zancanaro, son of Francesco, a 32-year-old peasant who was married with three children, collapsed to the ground from exhaustion. Word spread in an instant: a young man from Incino fainted, he simply couldn’t go on.

As often happens in these cases, an unforeseen event can change the tenor of a crowd. A brother of the man who fainted, Agostino, barely more than 20 years old, ran toward the belltower shouting “Sound the alarm bells, or we’ll perish here one by one!” Several people followed him trying to get into the belltower but failed, since moments earlier the pastor had locked it out of precaution.

At the sound of the alarm bells, the crowd would have surged—and might have changed its temperament.

Conscious of the danger that taking over the belltower would carry a forceful symbolism, Rocca’s pastor personally intervened to stop it: “But I fended it off,” he later declared to Chancellor Mengotti, “with all the force of reason and persuasion, and fatefully diverted their attack.”

After reviving the unconscious young man, Don Leonardo had everyone go into the church for mass. In church, another person in the crowd fainted from hunger: a certain Giacomo Grando, whom the pastor called “a thief, a disturber of the peace, and extremely wretched,” and whom the others described as “a beggar.” Possibly since they were in church, or more probably since he was a beggar, this incident didn’t provoke a reaction like the one in the piazza minutes before.

As everyone left church after mass, the Deputy and the Chancellor, back from collecting donations, were having the polenta prepared. Another person fainted during the wait, but by now it was only a matter of time, and the polenta was served to everybody, though it’s unclear whether it was on the piazza or inside the church. It was enough that word spread about food to eat in Rocca, and immediately families rushed over from the districts of Incino, Corlo, and Berti.

Toward noon, the crowd of 120 was joined in the piazza by 50 more, and the witnesses agreed that half of these were women and children. Many—a good half of those present—came to the piazza only when they learned there was food. A peasant from Incino, Antonio Zancanaro, who had to go down to the plain that day to look for work, was so weak from hunger that he couldn’t make the trip. But when he learned that they were making polenta in Rocca he went over around noon, and only the next day did he set off on his journey.

Other people happened to be passing through Rocca then and stopped just in time to eat their share, like a certain Giovanni Maria Fantin from Corlo who, the pastor recounted, came an hour after the others with a bindle on his back and was moving to Longarone to become a coal miner. He reached the piazza, and, told they were making polenta, stopped to eat it and then continued on his way.

Over the following days, the Chancellor of the Census of Fonzaso proceded to interrogate ten men who were arrested, nine of whom were from Incino. Further testimony was heard from Town Deputy Gervasio Arboit, his wife Angela, Town Councilor Giacomo Grando, and pastor Don Leonardi.

The witnesses were in agreement that the disturbance was the result of hunger and ruled out any other motives. Mengotti pushed to verify “whether the insurgents fostered any anti-government intentions,” but the answers were all in the negative.

Asked “whether the crowd had aims outside of obtaining contributions from the landowners,” Deputy Arboit answered: No aims beyond providing for their hunger. Indeed, among the insurgents there were many individuals who appeared haggard and cadaverous, who displayed genuine need and hunger.

Pastor Don Leonardi provided a startling picture of the misery in that year of famine:

They didn’t have aims, other than living in some meager way and not dying in their hovels. Many are in fact already dead from this cause, and many more are close to death. I administered last rites even today, and I am sadly sure that I will have to do the same every day unless a special providence arrives. Otherwise I predict, and I am certainly not deceiving myself, that half of the population (of Incino) will have succumbed from this cause.

The arrested suspects were all men, “peasants” by trade, and “illiterates” who didn’t even know how to sign their own names. Two were 18-year-olds, one was 40, and the others were between the ages of 23 and 32. Everyone defended themselves declaring that there was no premeditation, that everything happened all of a sudden, and that they personally had gone to the piazza because they were drawn by the people who were there.

One turned up at noon hearing that polenta would be given out, another was passing through Rocca on his way back from the pharmacist in Arsiè to buy medicine for his father, yet another saw the crowd coming down the road while he was working in the fields. If they were involved in the mob it was for the sole purpose of obtaining relief to survive.

24-year-old Alvise Nardino from Incino declared:

Many women and children joined in the crowd, and it was such a pitiful thing to see so many people collapsing from starvation. It shows that the assembly was stirred by hunger, the result being that as soon as we were given a little polenta and flour we all returned to our houses, and then surrendered based on innuendo from the Town Deputy and the local pastor.

Mengotti wanted more precise information about the organizers, but none of the accused could point to who they were. More easily learned were the names of many participants, largely thanks to initial witnesses who displayed a great knowledge of the villages’ residents, families, and degrees of kinship. At the end of the questioning, Mengotti was able to identify about 70 participations—namely those who were first to go down to Rocca.

Everyone was asked “if he knew that among the mutineers there had been someone threatening to sound the alarm bells.”

The accused flatly denied it—to admit this would mean that someone did in fact want to create a disturbance in order to seize grain and flour from the landowners. The only one among them, perhaps intimidated by the tone of the interrogation, 24-year-old Alvise Nardino, confessed to having this intent along with the two young Zancanaros whose brother had fainted from hunger. But he immediately toned down the significance:

Several people had this aim, but only to unite the people and provide for their need. Among these were myself, Agostino Zancanaro, and his brother Bortolo. I myself heard them shouting to ring the bells but it didn’t happen because the belltower had been locked.

There were 16 people arrested for the events in Rocca, all men. About one month after their arrest, the Court of Belluno reviewed the crime of insurrection for which they were charged. It was decided that they should not punish those who only formed part of the resulting crowd, just the most persistent, but above all the ones who had even proposed sounding the alarm bells.

Furthermore, it was decided that instead of bringing them to trial, it would be sufficient to sentence them to precautionary detention. Thus 7 residents of Incino were transferred to the Giudecca prison in Venice and served a sentence of 3 months. (Or 4 months, according to another source.)

Finally we must add that in addition to the clampdown, the Chancellor of Fonzaso had aid delivered to the town of Rocca in the days immediately following May 19th. He sent £300 and 24 sacks of lentils and fava beans to be distributed to Incino’s poorest residents. The Delegate of Belluno did the same and sent £550.