The History of Incino

1700 – 1886: Shifting Empires

1700

On May 23, a double tragedy is reported in Incino. Lucia Zanchanaro, about 36 years old, wife of Giacomo, died with her 8-year-old son Domenico. They were both buried when their house collapsed just before midnight.

Note that there are no transcription errors in the Italian from that time. Curious how the last name Zancanaro was recorded: from 1700 to 1744 it was written “Zanchanaro,” while the current last name Nardino was written “Nardin.”

1745

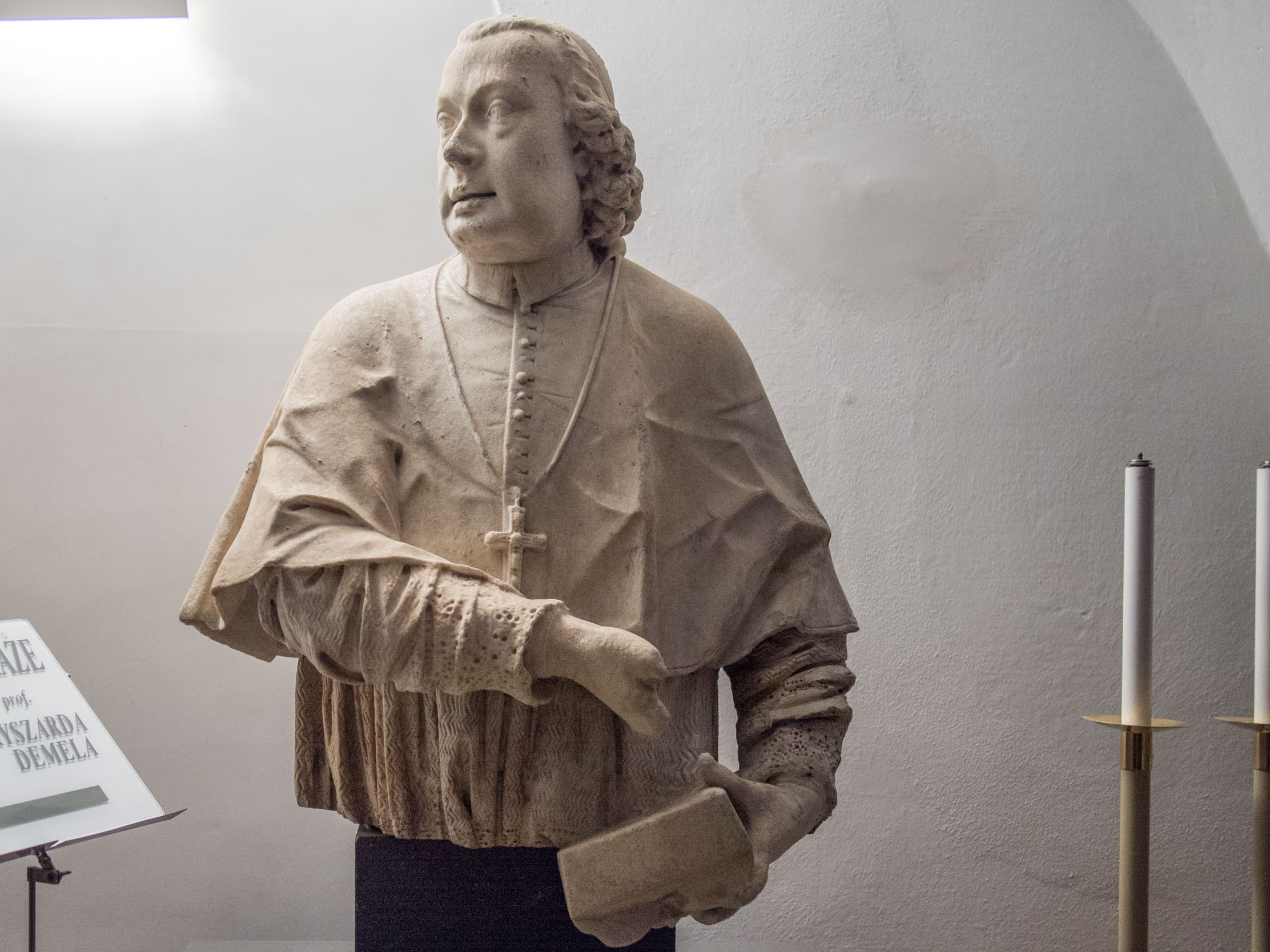

At the end of July, there was a pastoral visit to Arsiè from the Bishop of Padua Cardinal Rezzonico (the future Pope Clement XIII). The archpriest at the time, Don Giovanni Forcellini, informed the cardinal of a grievous abuse: the districts of Corlo and Incino were not sending their children to religious school in Rocca. There were yet further complaints, since instead of praying for rain in the organized drought processions from Arsiè, the residents of Rocca and Incino would appeal to saints outside the parish for relief (probably visiting San Vito to pray to the martyr saints).

In that year Rocca and Incino had 1,001 inhabitants, the youth were lively and had the ugly habit of going to mass adorned with flowers.

1748

On August 18, after a week of continuous rain that swelled the Cismon River above its banks, an enormous volume of water bore down on Cismon: 37 houses were flattened, the parish church of San Marco was severely damaged, the chapel of Pedancino al Ponte was destroyed, and the statue of the Madonna was swept downstream to Frivola di Pozzoleone. Here it was found intact and in the following days it was brought back to Cismon to great emotion from the population, which held its retrieval to be miraculous. In response, a decennial celebration was organized that continues to be observed to this day.

What no one remembers is that the chapel of Pedancino was located in the parish of Rocca but it was subordinate to the parish of Arsiè. At that time, the township of Rocca occupied the entire right bank of the Cismon, indeed, during later decennial celebrations, mass would be celebrated by a prelate, but Rocca’s pastor could only assist while acting as a deacon, because at the moment of the great flood the sanctuary belonged to his parish, and it in turn has since become filial to the church of Santa Maria Assunta in Arsiè.

1766

A group of criminals assembled in a band and terrorized Enego, Foza, and the entire Brenta River Valley. They swept through the Feltrino and into some Trevisan districts as well. Leading the band was Marco Antonio Bertizzolo, known as Alban, or Bano. His base was in Enego, but he also relied on safe houses in Incino, Corlo, Fastro, and Zanetti, and in the Seren Valley too. He seemed unstoppable.

Venice ordered that he be driven out, in vain—until it put up a large bounty.

While Bano was playing cards in Primolano one day, an informant reported his movements and mounted guards burst in. At first, Bano managed to escape—he attempted to return to Enego, fleeing his pursuers. But he sustained a wound to the foot and he was overtaken. They dragged him back to Primolano where he died bleeding.

As the guards were on their way to Bassano to collect their bounty, they were intercepted in Vastagna and were annihilated. But Bano’s exploits were over and his men scattered. Some passed through the territory of Arsiè, but Venice ordered Captain Antonio Crotti from Feltre to clean out the area of Incino, Rocca, and Corlo, and during a sweep on the Incino–Corlo bridge, the bandit Pietro Guerra, a close friend of Bano, was captured. He was imprisoned in Feltre and then in Venice, to be hanged in Piazza San Marco.

1785

Cultivation of the potato begins throughout the Feltrino.

1809

The Austrians drove the French out of the Feltrino after a skirmish in the piazza in Arsiè. One Napoleonic company, repairing to Bassano as fast as possible, stormed through Rocca and Incino.

1815

The Fall of Napoleon

A congress was held in Vienna by the victors to establish a new order in Europe. Among many decisions, one applies to us: Lombardy and the Veneto were assigned to Austria, and Incino—along with the whole territory of Arsiè—was absorbed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Immediately the province of Belluno was established with genuine administrative autonomy. The province was divided into districts and townships; the sixth district (capital: Fonzaso) comprised the following townships:

- Fonzaso and Arten

- Arsiè

- Rocca, along with Incino, Fastro, and San Vito

- Mellame and Tovio (Tovio was the old name of Rivai)

- Lamon

- Arina

- Servo and Sorriva

In the time that Rocca was a township, the town council was called “The Rule” and consisted of 20 men, among whom:

- 4 were zuradi (responsible for public order and surveillance of foreigners)

- 2 were saltari (forest and field guards)

- 2 were cercamainenti (border guards and peacekeepers in boundary disputes)

- 2 were massari (tax collectors and asset managers for the churches and brotherhoods, as well as keepers of the alms that were distributed every six months)

- 1 was a quaderniere (a town secretary who recorded all decisions)

The Rule, which usually met on the eve of a religious holiday, was chaired by the mariga (the mayor) who controlled town property, disbursed the tax revenues, enforced the laws, and could conscript male citizens to build roads and bridges and other public works for the common good.

The only tax was the “colta” (as in raccolta, meaning “collection” or “harvest”), and its only subjects were heads of households. Bells were rung before all public meetings, a custom that endured until 1926 when it was abolished by Fascism.

Thanks to this period of far-reaching peace after the Napoleonic whirlwind, the population expands more than ever, with tiny hamlets built out to the most remote places as long as there was a bit of arable land. In these years (between 1815 and 1850) the settlements of Tanisoi, Prai, Martinati, and Pomer spring up.

1816

This year a severe famine struck the entire Feltrino. To revive the depleted economy, Austria intervened with considerable aid, permitted the growing of tobacco, which until then was highly prohibited, and embarked on many public works, the most important of which was the straight stretch of the Culliada Road.

The situation in Incino was so desperate that the residents “besieged” Rocca, the town seat of Arsiè, begging for food. A deputy and a town councilor solicited polenta and cheese from the most well-to-do citizens and managed to subdue both the hunger and the revolt.

1817

The fresco of the Madonna di Loreto surrounded by a large frame was painted this year on the side of an apartment block in Tanisoi. The current state of preservation is poor—the fresco is now unintelligible. The artist is unknown, but the same person who produced the work in Tanisoi painted another 10 years later in San Donato di Lamon, dated 1827.

1818

On September 12, the Austrian emperor imposed compulsory education on all children in the empire between the ages of 6 and 12, and ordered that each school have a schoolmaster with a minimum of 50 pupils per class and a maximum of 100. The following year Incino’s children started attending school in Arsiè.

1822

According to a document kept in Rocca, among Incino, Pomari, and Casere, there were 66 families in residence thus subdivided by surname:

- Zancanaro: 33

- Grando: 13

- Nardino: 11

- Borsa: 3

- Rech: 3

- Stieven: 2

- Martinato: 1

- Strappazzon: 1

1824

The townships of Arsiè, Rocca, and Mellame are dissolved and the township of Arsiè in its present form is born. At this time, Rocca and Incino had a little more than 2,000 residents.

1837

On November 12, the death of Domenico Zancanaro, known as Coa, is reported. He was 30 years old. Curious where he died: in Incin di Sotto, “Under Incin.”

1848

On June 6, the Austrians restored the bridge over the Cismon linking Arsiè and Feltre.

Fastro, Incino, and Corlo are torched in retaliation for their resistance movements, “because they fired at the backs of soldiers.” Arsiè was merely sacked.

1866

At the end of the Third War of Independence, on October 8, Incino became Italian. On October 21, the plebiscite was held to sanction the annexation of the Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy. In Arsiè, which then counted 5,704 residents, all 1,359 voters unanimously voted for the handover to Italy. From subjects of Franz Josef, they became subjects of Vittorio Emanuele II. Austrian domination lasted for 51 years.

1870

In Prai d’Incino, a shrine dedicated to Saint Anthony of Padua was unveiled. It’s a tile-roof kiosk protected by a wooden gate. The fresco painted on the back wall has vanished, replaced by a print of Saint Anthony and Child. On the outer walls there are two small niches that had been frescoed but the paintings disappeared under a recent whitewash.

In the years following, on a house in Prai facing Enego, a fresco was painted depicting a young man (possibly San Vito) in front of a large Romanesque-Gothic church. This painting will be destroyed in the house’s renovation.

In those years the shrine near Casere was still being built at the intersection of the old road to Prai, which was first dedicated to the Madonna Assunta but now bears effigies of the Sacred Heart of Mary and Saint Anthony. In the background there was a painting that is now lost: State of conservation: poor.

Finally, at the end of the Century, the crucifix was put up at “il Cristo” with a wooden sculpture for the likeness, two square beams for the cross, sheet metal for the roof and back, set on a large stone base. It measures 265 cm by 140 cm, with an alms box at the pedestal. It was built to mark a station where the Rogation processions would pray for harvests. The spot is now commonly called “il Cristo,” rather than its earlier name of “la Forcelletta.”

Ultimately, after total neglect and abandonment undermined the very stability of the work, a private party intervened to completely restore the crucifix and prevent historical memory from being lost.

1871

In Rome, the Permanent Parliamentary Commission for the Defense of the State devises a plan to fortify the border with Austria and marked 47 points in the area generally known as “Primolano” (one was Incino) to erect new barricades. A sum of 1,300,000 lire was allocated.

1873

While the new church in Rocca was under construction (later demolished for the dam), the Rocchesani signed a £2,059.86 contract with a quarry in Val Nevera for a supply of paving slabs, but, having already incurred other debts, the cost was shouldered by the districts of Incino, Corlo, and Carazzagno.

1881

The most illustrious citizen of Rocca, Angelo Arboit—priest, patriot, Garabaldino—writes a 40-page pamphlet entitled Italy on the Eve of a European War. In essence the author, addressing the Honorable Pompeo Alvisi, Feltre legislator, was encouraging a new road to be built between the Feltrino and the area of Bassano which would pass through Incino and replace a zig-zagging path that could not be crossed even on foot without danger (so much that more than one person who lost his footing had lost his life at the bottom of the Cismon).

The motivations were twofold: military, to allow the army to bypass the Scale di Primolano and proceed straight to Bassano; and economic, permitting the mountain residents to sell their goods directly to the plain.

In those years the township of Arsiè was producing between 30,000 and 40,000 hectoliters of wine, which, with a new road through Incino, could be sold for 100,000 lire above its former prices, no longer weighed down by buyers’ circuitous detour through Primolano.

1882

On May 20, Nardino Abramo dies at the age of 52. He had been admitted to the hospital in Belluno for an attack of illness while in jail there, serving a sentence for tobacco smuggling. He is probably the first man from Incino to be hospitalized.

1883

At the explicit request of the Honorable Alvisi, a delegation from the Military Commission for the Defense of the Alps arrived in Incino and approved the Arsiè–Cismon Road for construction, which would pass through the villages of Rocca and Incino and incorporate numerous tunnels.

This year a census was held; the population was divided thus:

- Arsiè: 1,883 inhabitants

- Mellame: 967

- Fastro: 832

- San Vito: 610

- Rocca, Incino, and Corlo: 2,359

1885

In Rome, the Minister of War General Ferrero presented the “General Plan for the Defense of the State” in parliament, which identified regions and locations where fortifications should be built. From our parts, Primolano, Fastro, Prai d’Incino, il Tombione, and Faller were mentioned.

It was decided that north of Prai, on the slopes of the Col del Gallo, a clearing would be built from which artillery could, under fire, hold Enego and the Piovega Road, as well as strike the basin of Cismon. It was equipped with 5 mortars with 2,000 rounds and 6 cannons. The remains of these fortifications can be seen just at the foot of the big RAI antenna.

On December 29, a dispatch from Carabinieri Command in Sciaccia (Legion of Palermo) arrived in Incino reporting the death of Giacomo Zancanaro, son of the late Domenico. Cause: intentional suicide. He had been the first man from Incino to be admitted to the armed forces.

1886

On January 20, there was anguish in Incino over a man’s death, but it could have been a massacre. The events, as reported in words of the death register:

Giacomo Stieven, son of Luigi, born on January 24, 1814, widower of Santa Menegaz, daughter of Rasai, died under an avalanche of snow at 10 in the morning and his body was found at 4 in the afternoon, Stieven left the district of Incin to go to his farm located in Costa, he came over the fountain of Incin, it isn’t known how, and he was swept away by the avalanche, which hurled him down through the Valle della Fontana, two other boys and a girl were buried under the same avalanche in front of their fathers, who weren’t able to rescue them. Luckily, all the men in Incin were assembled there to clear the streets of snow, and alarmed by the calls for help they rushed over and came to the rescue, the three children were soon found, still alive, meanwhile a voice called for help in the Pomer district, which carried to Col, Col ai Berti, and Berti alla Rocca, here, too, the able-bodied men were already assembled clearing, they got news of what happened, they all rushed to Incin to lend a big hand to the rescuers, and after six hours of uninterrupted work they retrieved Stieven’s body in the middle of the valle.